How much Is left to discover? Crystal prediction in a quaternary search space

How much Is left to discover? Crystal prediction in a quaternary search space

Promotor(en): S. Cottenier /15_MAT01 / Solid-state physicsHow many different (crystalline) solids can be made by the about 90 elements we have at our disposal? Let us simplify the situation in order to make an estimate: we consider only solids where every element in the chemical formula appears only once (e.g. NaCl or FeAsS, not TiO2) and we ignore the degree of freedom offered by crystal structure (i.e. graphite and diamond are considered to be the identical). Under these simplifications, how many different ternary solids could exist? The answer is 117 480. That’s a lot, but it is vanishingly small when compared to the number of solids with 45 different elements: 1.04 × 1026. Nevertheless, the largest experimental crystal databases (which contain way over 100 000 entries) list ten thousands of ternaries, but not a single crystal with 45 elements.

That’s strange… It looks like there is a driving force that prevents the existence of crystals made from too many different elements. And indeed, that driving force exists – it’s left as a little challenge for you to identify it.

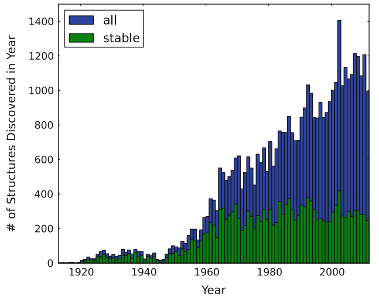

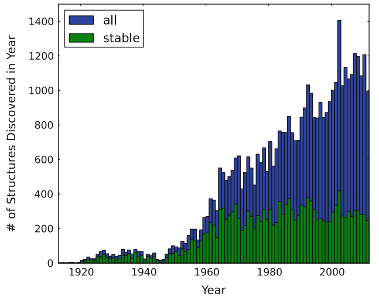

How many of all possible crystals do we know yet? Is there still a myriad of new solids waiting to be discovered, and can engineers therefore dream about many new materials with marvelous properties to solve current problems? Or do we know nearly all possible crystals, meaning that we are bound to solve our problems using not much more than what we have already? The saturation observed in the discovery rate of new ground state structures of crystals (see figure, from Saal et al., JOM 65, 1501 (2013)) suggests that we are reaching the boundaries of the set of discoverable crystals.

Quaternary crystals lie on the edge between the known and unknown crystals. Knowing how many of all potential quaternary crystals effectively exist will give a strong indication whether quaternary or rather quinary or senary crystals form the upper end of possible crystals. The quaternary family is huge, way too large to screen systematically in an experimental way. That’s why we have to resort to computational screening using density-functional theory.

Goal You will investigate the class of quaternary crystals formed by combining an alkali or alkaline earth metal with 3 elements from groups 13 to 16. About 250 crystals of that class are experimentally known. Your goal is to find the (many or few ?) undiscovered crystals in some well-defined subclasses. In the likely event that you find new crystals, your results might trigger experimental follow-up work to synthesize these. The number of crystals you find will contribute to answering the question whether or not the quaternaries are the last major group of crystals. Within the dataset of stable and metastable crystals that you will have produced, you will be able to search for stability hotspots and trends of properties across the set – this insight might suggest where to search for crystals with optimal values of a given property. Your calculations will be done in such a way that the results can be added to existing computational databases, where they can be retrieved and used by future researchers.

- Study programmeMaster of Science in Engineering Physics [EMPHYS], Master of Science in Physics and Astronomy [CMFYST]ClustersFor Engineering Physics students, this thesis is closely related to the cluster(s) Modelling, materials, nano